Elite sportswomen chasing medals on ‘less than minimum wage’

- by Admin

- March 25, 2024

Imagine chasing top medals and trophies for Great Britain while earning less than the minimum wage.

That might sound surprising yet it appears to be the reality for some women competing at the highest levels of sport.

More than a third of 143 respondents in a BBC study of elite British sportswomen said they have considered giving up sport because of the cost of living crisis.

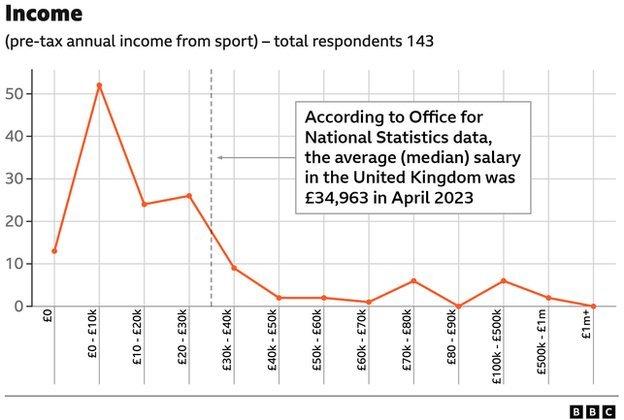

More than three-quarters said they earn less than £30,000 a year from sport – with more than four in 10 earning less than £10,000 and six in 10 earning less than £20,000.

According to Office for National Statistics data, the average salary in the United Kingdom was £34,963 in April 2023. The national living wage for someone aged over 23 working a 35-hour week would be up to £18,964 a year.

The BBC study, released on Monday, covered a wide range of issues affecting sportswomen, which we will be covering in a series of stories this week.

Respondents were asked to fill in an anonymous questionnaire. It was sent to 615 athletes across 28 sports and 143 responses were submitted.

The questionnaire was sent to British sportswomen above the age of 16 who compete for their country in senior sport, or at the highest level in their sport at top club level.

It is the fourth time the BBC has conducted research on elite British sportswomen, having previously done so in 2013, 2015 and 2020.

Below are some of the experiences athletes shared with the BBC about the impact of the cost of living crisis, social media trolling, sexism and maternity in sport.

Chasing medals on ‘less than minimum wage’

One athlete, who is aiming to qualify for the 2028 Olympics and has won junior world titles, told BBC Sport she had “thought about” quitting sport because of cost but is “not ready to”.

She says the starting salary for a job in the field she has studied at university would be more than double what she currently receives in funding for her sport.

“You’d never think I’d be on less than minimum wage,” said the athlete, who receives funding of £16,000 a year.

She added that while she should probably get a job on the side to support herself, it simply was not practical because of training times.

“I’d have to work night shifts – you’re not going to get international medals if you’ve got to do that,” she said.

She added that the current economic climate made it “hard” to get sponsorship and that her male counterparts seemed to get more sponsorship than women “even though their achievements are the same”.

Her views were echoed by others, with one respondent writing: “As much as the profile of women’s sport is on the rise, in the smaller sports, sponsorship is decreasing and making it harder to survive even with world-class results and world top-10 rankings.”

Another sportswoman spoke of working five jobs to fund her sport, and another said she had struggled to get sponsorship early in her career because she did not have the right body for “bikini modelling”.

Six respondents said their income was between £100,000 and £500,000, two put theirs at more than £500,000 but none made more than £1m.

According to the study, more than three-quarters of respondents felt sportswomen are not paid enough compared with sportsmen.

“If a female sportsperson is doing exactly the same training as their male counterpart, but they get paid less, then it will always mean that women are underpaid compared to men, but I do believe it is all going in the right direction,” another anonymous response read.

‘Requests for naked pictures’ and ‘I know where you live’

More than a third of respondents said they had been trolled on social media and a quarter had received social media abuse of a sexual nature.

One athlete was trolled after what she said was a result of people betting on her matches.

“Some matches, if it was a big win or big loss, I’d get 15-20 people messaging me on Instagram or commenting all sorts of things,” she said.

“A lot of it was about weight, sometimes people would comment on my upper body being leaner than my lower body.

“Some of it was, ‘I’m going to find your mum and do x, y and z. Some of it was, ‘I know where you live.'”

Another anonymous athlete said they “receive an influx of sexual abuse” after winning medals and another said they had received “requests for naked pictures” and “offers of sponsorship or funding in return for a relationship”.

While not directly comparable, a BBC questionnaire in 2020 found 30% of elite British sportswomen had been trolled on social media, a figure that had doubled since a previous questionnaire in 2015.

‘I was told my award was for best bum’

Sexism offline is still a concern for sportswomen too, with almost three quarters of respondents saying they had experienced sexism in their sport.

“I’m just so shocked, I’m just on the edge of tears,” one athlete told BBC Sport when recounting the time in the past few years that she had gone up on stage to receive a top award for performance and the presenter had announced it was for having the “best bum” in her sport.

“[It was] in front of a room of all the people that I looked up to and aspired to as a young female,” she said. “[I wanted to] just get it over with, just let me get off the stage. Now I know what to say. But then I definitely didn’t.”

The study also found sportswomen felt they were being treated differently to men in terms of coaching.

A third said they did not get enough coaching support compared with men, and a third said their governing body does not support them equally compared with male colleagues.

More than four in 10 said they had experienced another form of discrimination.

Maternity ‘feels taboo’

More than a third of respondents said they do not feel supported by their club/governing body to have a baby and continue to compete.

Almost two-thirds do not know what their club/governing body’s parental leave policy would be.

One sportswoman said the topic of maternity “feels taboo”, another felt their career might be “in doubt” if they brought up the issue, and another said their governing body “has repeatedly put off signing our maternity policy”.

A third have delayed starting a family because of their sporting career. Six women said they had had an abortion because they felt a baby would impact their sporting career.

One athlete said she was returning to sport a year after giving birth and had been “severely let down” by her governing body, which had “not been willing to compromise” or understand her needs.

Another said her decisions around maternity were based on “fear of time out of sport and fear of not returning”, and another said theirs were around the cost of childcare she would need to continue training.

However, one anonymous response came from a mother back in full-time training after having a baby.

“There is a very good balance to allow me to train a week full-time in the environment and a week training at home, which helps with being an athlete and mum,” she wrote.

There was another example of a national team saying they would support athletes wanting to give birth and “return to sport in the quickest and healthiest way possible”.

Is any progress being made?

Sportswomen highlighted many challenges in their responses, but several pointed to the success of the Lionesses’ high-profile Euro 2022 win as a sign of progress.

When it comes to media coverage, three-quarters do not believe the media does enough to promote women’s sport, but more than nine in 10 think media coverage of women’s sport has improved over the past five years.

Sports minister Stuart Andrew said he would be convening the first Board of Women’s Sport later this month, where “former sportspeople, industry experts and academics come together to explore opportunities and best practice” for women’s elite sport.

“We are at a defining moment for women’s elite sport in this country,” he said. “I want to see it continue to go from strength to strength, with a collective drive to deliver positive change.”

Triathlete Laura Siddall spoke of an expectation of women’s sport to “be grateful for where you are now”.

“I think we can be grateful, but that doesn’t mean we’re satisfied,” she continued.

“We are super thankful that we’ve made huge progress and super thankful and grateful that we are here now, but does that mean we should be settling? Because there’s still a disparity.”

Graphics by Lee Martin

The Latest News

-

December 22, 2024Donald Trump picks Apprentice producer to be the US special envoy to UK

-

December 22, 2024Daily horoscope: December 22, 2024 astrological predictions for your star sign

-

December 21, 2024UK flights and ferries cancelled owing to high winds as Christmas getaway begins

-

December 21, 2024Prince Andrew plans to move to UAE amid espionage allegations: Report

-

December 21, 2024Inside Britain’s saddest shopping centre: Town centre mall empty just DAYS before Christmas as depressed locals say ‘it’s a disgrace’