Of the eight climbers huddled together at the bottom of the overhanging 15-metre wall in Paris, there was one who was there because he carried the dream of winning an Olympic medal.

For many, their journeys into the sport largely started because of a natural instinct rather than the buzz of competition. Great Britain’s Hamish McArthur, for example, could not stop clambering up trees or hanging off door frames as a child. Toby Roberts was not too dissimilar. He would attempt to escape his cot as a baby, before he topped his first wall at three years old, well before the point he knew what he was doing was a sport at all. Unencumbered by any sense of fear, he wanted to climb as high as he could, because that was the only direction he thought to go.

By the age of 12, Roberts and his father Tristan had already formed a plan. When sport climbing was introduced to the Olympics in 2016, Roberts and his father set their sights on winning gold in Paris. Eight years later, he stood as Britain’s first Olympic champion in sport climbing: mastering the combination of lead and boulder after displaying supreme skills across problem-solving, strength, agility and endurance. It was the fruition of a childhood dream and a long-term goal.

“It’s been a journey,” he said. “A lot of competitions, a lot of ups and downs. But to finally be on the stage, competing in front of this crowd and to win the gold medal was just like a dream come true.” After an excellent performance across the four problem sets on the shorter, 4.5-metre bouldering wall left him in third place, Roberts reached the upper section on the longer lead climb to strike gold for Team GB. He set an imposing combined total that Japan’s 17-year-old contender Sorato Anraku could not surpass.

Roberts is sometimes nicknamed the “Terminator” – he does not remember why it stuck, or who gave the nickname to him, but his performance on the wall in claiming gold suggested its origins lay in his composure and machine-like endurance. Afterwards, there was shock. “Going into the competition, I tried to remove all expectations,” Roberts said. “To realise I’d won the gold, there was just a rush of adrenaline and emotion and happiness. I’ve been working towards this for like 10 years.”

Roberts had predicted that the new format would crown the most “versatile” champion, and undoubtedly the combination of the two disciplines worked in his favour, while also producing one of the moments of the Olympics for Team GB. Roberts set the third-highest score in bouldering and the third-highest score in lead, behind the Czech great Adam Ondra and the world champion Austria’s Jakob Schubert, who both made it higher up the wall. But over the two disciplines Roberts produced the finest display all-around climbing skills that Paris wanted after the sport’s difficult debut in Tokyo.

In doing so, sport climbing found its home, returning to the country that gave birth to mountaineering and Alpinism centuries ago. Even at the Olympics, climbing remains a sport that is grounded by a sense of adventure rather than competition. Before the conclusion to the lead, for example, the eight finalists gathered together and discussed the route they were about to face, working together to ensure they were all prepared for what was to come. “We want to put on a show,” said McArthur, who finished fifth for Great Britain.

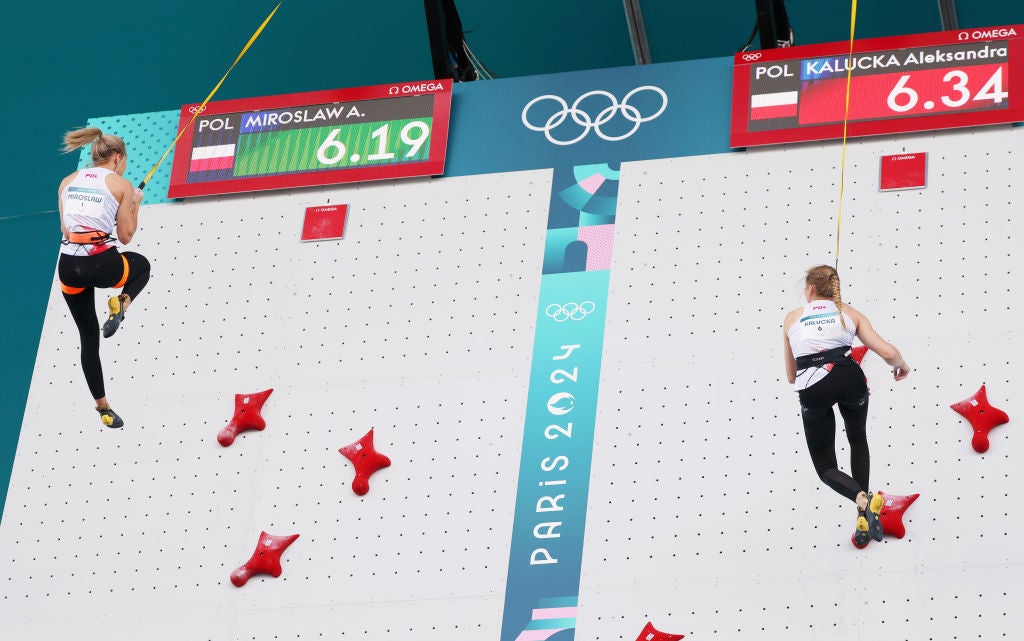

Climbing has been on a journey too. Three years ago, Aleksandra Miroslaw had a problem: at the Olympics, she found herself competing at a sport she was not good at. Miroslaw was a world champion in speed climbing, which that summer became the newest, and fastest, sport in Olympic history. But when it came to the other disciplines central to the inaugural combined climbing final, Miroslaw was out of her depth. Even the thought of lead climbing and bouldering was enough to make Miroslaw shudder and she laughs at the thought. “I’m so bad,” she sighed.

Three years later, Miroslaw became an Olympic champion. The Pole won the first ever speed climbing gold medal in Le Bourget, a north-eastern suburb of Paris, requiring just 6.06 seconds to race to the top of the 15-metre wall and conquer the route that was mapped away in the back of her mind. In changing her life, Miroslaw was dominant: winning every race she competed in and breaking the world record twice on her way to a historic gold. “It is a privilege,” Miroslaw beamed, ”to be the first speed climbing champion.”

For Miroslaw, having to compete in lead climbing and bouldering in Tokyo was like asking Novak Djokovic to take on the Olympic champion in badminton, or Usain Bolt to run the 10,000m. Her story was one of several that summed up climbing’s flawed introduction to the Games. With only one gold medal to award across the men’s and women’s events, the disciplines of bouldering, lead and speed were grouped together to crown a combined champion. The format proved to be highly controversial and was ridiculed by climbing enthusiasts.

For instance, the American Sam Watson, who also specialises in speed and won bronze in the men’s event while breaking the world record in 4.74 seconds, said Tokyo was like “trying to be a swimmer and a diver at the same time”. With the scores from each discipline multiplied together, one poor result in speed could eliminate a climber whose strengths lay in lead and boulder. Likewise, one outstanding result in speed could catapult a contender into contention.

Miroslaw finished fourth in Tokyo, narrowly missing out on a podium despite scoring zero points in lead and boulder. The men’s inaugural champion, the 18-year-old Alberto Gines Lopez from Spain, won gold largely because of his exceptional speed performance, which offset his low score on bouldering and relatively average performance on the lead wall. It was enough to lift Alberto Gines Lopez above two of the most accomplished climbers at the Olympics, in Ondra and Schubert.

Three years later, the Olympics rectified the format. There would be separate competitions, one for speed and another for boulder and lead, allowing the different skill-sets to be recognised in their own right. Over the last three years, Roberts had been focused on boulder and lead and becoming world youth champion in 2022 was a sign of how far he could go. Undoubtedly, living in relative proximity to the UK’s exact replica of “The Titan” wall used at the Olympics, in Wandsworth, was a bonus, but also a continuation of the long-term plan.

Roberts insisted victory would not change him but gold may help to further grow the sport in the UK, through the ever increasing number of indoor gyms and climbing clubs. “I hope it just makes climbing bigger and bigger,” he said. At the Olympics, it may have found its home as well.