Britain’s election could be historic. Here’s what to know.

- by Admin

- July 3, 2024

LONDON — Millions of Brits go to the polls Thursday, in an election likely to oust the Conservative Party that has dominated postwar politics and ruled the United Kingdom for the past 14 years.

Who governs Britain should matter to Americans. The U.K. is considered Washington’s closest ally, it is the world’s sixth largest economy, and it has a nuclear arsenal and a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council.

Here’s what to know about this pivotal vote.

The big picture

This election is being fought primarily between the ruling Conservative Party, which has been in government for 14 years, and the opposition Labour Party, which has not won a general election since the days of Tony Blair in 2005.

Every poll says Labour will win comfortably — with many of them predicting an unprecedented landslide. Conservatives are now openly conceding defeat before the polls even open.

Many voters say they are not being driven by love for Labour, however, but rather a deep dissatisfaction at the Conservatives.

For many in Britain, the country has long felt stagnant or broken: from the economy and public institutions like the crumbling National Health Service, to the sewage-filled rivers and the expensive, delay-ridden railways.

Many voters blame the Conservatives for this malaise and look set to punish them at the ballot box.

Who’s running?

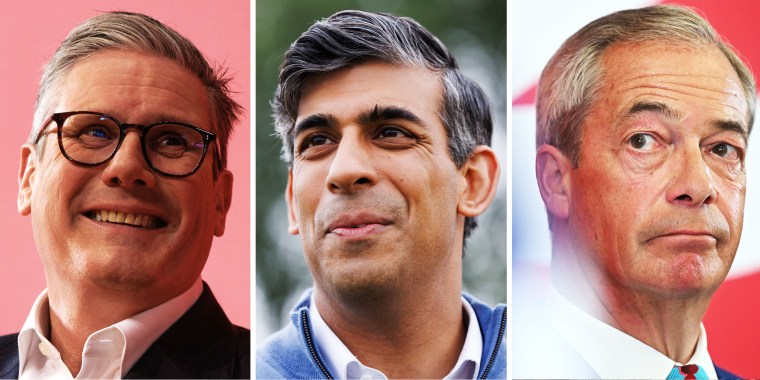

Conservative Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, 44, has led the country since 2022.

The son of Hindu immigrants of Indian descent, he became independently wealthy as an investment banker. But his wife — Indian tech heiress Akshata Murty — is the reason his family is now richer than King Charles III, with an estimated fortune of 650 million pounds ($820 million).

During the pandemic, Sunak served as finance minister to Prime Minister Boris Johnson, becoming the country’s most popular politician thanks to his furlough plan that paid the wages of millions of idle workers during lockdown.

Sunak became leader without a public vote after Johnson and then Liz Truss resigned in quick succession. But since then his personal polling — as well as that of his party — has slumped to record lows after a series of campaign gaffes.

Facing almost certain defeat, Sunak has been left trying to coax a disillusioned Conservative base just to turn up at the ballot box to prevent what he warns will be a Labour “supermajority” in the House of Commons.

It would be a shock if Sunak were not replaced by opposition Labour leader Keir Starmer, 61.

Starmer comes from a blue-collar background but would also be the first prime minister since the 1950s to already have a knighthood. He identifies as a socialist, but has angered many leftists after abandoning much of the progressive platform that made him Labour leader, such as privatizing utilities and railways.

He would be only the fourth person since World War II to defeat the Conservatives at the ballot box.

Aside from Sunak and Starmer, this year’s wild card is Nigel Farage, the populist whose critics label as far right. He’s an ally of Donald Trump’s and leads Reform U.K., an anti-immigration party that is poised to capture millions of votes from dissatisfied Conservatives on the right — but also some from Labour.

The Liberal Democrats, led by Ed Davey, will hope to mop up votes in the centerground. The Scottish National Party is fighting to hold its dominance north of the border, while the Greens and Plaid Cymru — the Welsh independence party — are expecting single-digit seat hauls.

What are the issues?

Principally: the economy.

Britain has been mired in a cost-of-living crisis. Real wages have flatlined for a decade — the U.K.’s average salary is just 29,669 pounds (about $38,000) — and prices have spiraled for utilities and food. Meanwhile, Britain has the worst rate of homelessness in the developed world, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, and 30% of children are growing up in poverty, government figures show.

Sunak says “brighter days” are ahead after inflation fell back from 11% in 2022 to the target of 2% last month. His party has promised cuts to taxes and public spending, which some economists say are unrealistic given how threadbare budgets already are.

Cautious of the Conservative accusation that it’s irresponsible with the economy, Labour has refused to raise income taxes. Some economists say if Labour wants to boost public services, then some sort of hike may be unavoidable.

Other key issues for voters are the NHS, which is beloved but underfunded and dilapidated, and rising immigration despite post-Brexit promises that this would fall. Meanwhile Sunak has staked much of his manifesto on a controversial plan to deport asylum–seekers to Rwanda, as well as introducing mandatory national service for 18-year-olds.

How does it all work?

Whereas the United States elects its president and Congress separately, in the U.K. these are rolled into one. Although Labour and the Conservatives dominate, there are 28 parties taking part.

The British general election is actually 650 mini-votes spread out across the country. Each small constituency chooses one member of Parliament representing that area and the party with the most MPs usually forms a government.

One lawmaker from each party has already been chosen as its leader, usually in a byzantine internal process, and the leader of the largest party becomes prime minister.

This system is called “first past the post” — essentially most-votes-wins in each of the 650 constituencies — and it can throw up some wild discrepancies.

For example, if a party polls well nationally but fails to win any one constituency, perhaps recording a slew of second places, then it would not get any MPs. By the same model, some forecasts have Labour winning 37% of the vote but a full 70% of seats. It’s by this same quirk that Farage’s Reform U.K. party is unlikely to win many seats: They will have plenty of strong showings but few outright constituency victories.

If any party fails to win a majority, they may have to enter into a coalition with a rival, but this is unlikely to happen this time given Labour’s commanding lead in the polls.

The Latest News

-

December 22, 2024Donald Trump picks Apprentice producer to be the US special envoy to UK

-

December 22, 2024Daily horoscope: December 22, 2024 astrological predictions for your star sign

-

December 21, 2024UK flights and ferries cancelled owing to high winds as Christmas getaway begins

-

December 21, 2024Prince Andrew plans to move to UAE amid espionage allegations: Report

-

December 21, 2024Inside Britain’s saddest shopping centre: Town centre mall empty just DAYS before Christmas as depressed locals say ‘it’s a disgrace’