Cool Britannia: Life in the UK when Labour last triumphed over the Tories

- by Admin

- July 7, 2024

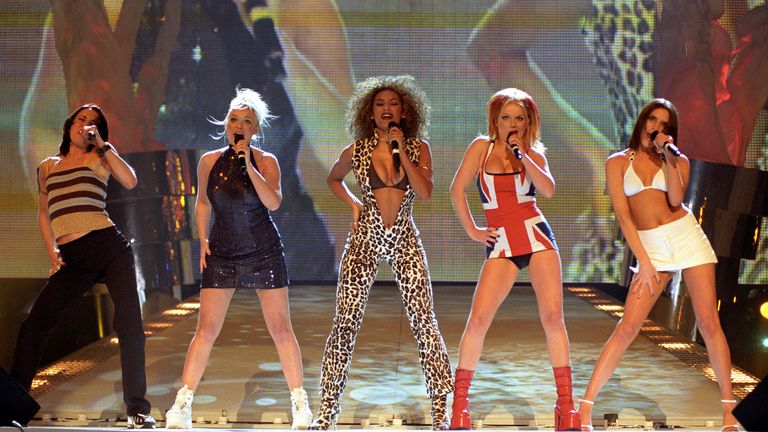

An unknown book about a boy wizard, Harry Potter, rolled off the presses, its publishers expecting to sell just 500 copies. Paparazzi hungered for exclusive photos of Princess Diana. And everywhere, you heard the Spice Girls telling you to spice up your life.

The year was 1997 and it was the last time, until now, that Labour had seized power from the Tories, kicking a Conservative prime minister out of Downing Street.

Then as now, Labour won a landslide victory, ending more than a decade of Tory government – 18 years in 1997 and 14 years now.

But while it’s tempting to draw parallels between Tony Blair and Keir Starmer, much has changed in Britain in the last 27 years.

Blair inherited from his Tory predecessor, John Major, a healthy economy, and started his premiership in a decade of relative stability and prosperity.

Starmer has to grapple with a cost of living crisis, the aftermath of Brexit and the COVID pandemic, and at least two major global crises in the wars in Ukraine and Gaza.

“The national mood is very different,” said Adam Boulton, political commentator and Sky News’ former political editor.

“1997 was optimistic, summarised by Labour’s unofficial campaign anthem Things Can Only Get Better.

“2024 is pessimistic – the song has resurfaced but more in the sense of, ‘things can’t possibly get worse – can they’.”

Cool Britannia

Tony Blair was first elected in May 1997 – at 43, he was a youthful prime minister who promised a “new dawn”. The approach of the new millennium added to a sense of excitement.

“It felt as if a fresh era was beginning,” Blair wrote in his memoir A Journey, recalling the enthusiasm of a crowd assembled outside No 10 the day after he won the vote.

“It ran not just through the crowd but through the country. It affected everyone, lifting them up, giving them hope, making them believe all things were possible.”

The economy was growing and inflation was low. The age of Cool Britannia amplified Britain’s soft power: Britpop bands like Oasis and Blur were fighting for dominance of the charts, and the Spice Girls were at the height of their girl power.

Harry Potter And The Philosopher’s Stone was published in June, the start of a multi-billion-pound franchise that would grow to include more novels, movies, and spin-offs.

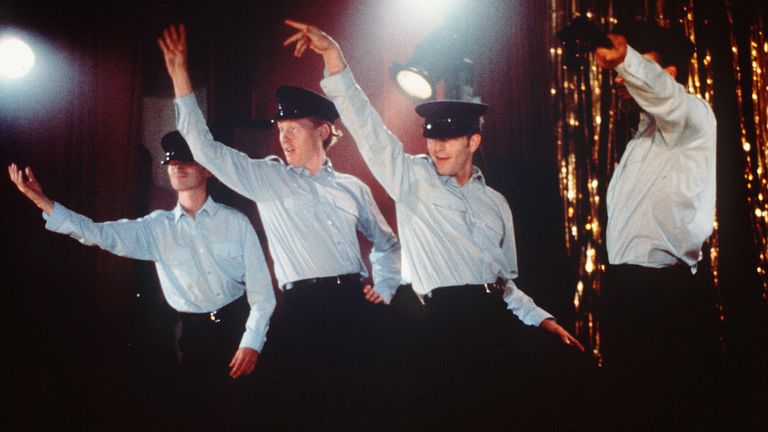

In cinemas, a film about a group of unemployed steel workers becoming improbable male strippers, The Full Monty, warmed hearts in Britain and beyond, while Pierce Brosnan was busy saving the world as 007.

Titanic would be released in time for the Christmas season in the US (and not until the following year in the UK).

Katrina and the Waves won Eurovision with the song Love Shine A Light – the last British act to do so.

Blair would at the same time ride the wave of Cool Britannia and embody it.

“The nation seemed to share in the changed mood,” says Boulton.

“There was real positive enthusiasm for Tony Blair, the clean-living young US-style candidate, shirt sleeves rolled up,” he adds. “He couldn’t go out in public without being mobbed.”

By contrast, “this time Labour canvassers reported that there was little enthusiasm for the party ‘on the doorstep’ – just a sense that the Conservatives’ time was up”.

In August, the death of Diana in a car crash in Paris traumatised Britain, and Blair, coining the phrase “the people’s princess”, embodied the national mood of grief.

Years later, things would sour for Blair, too, for good.

The country turned against him and his decision to follow then US president George W Bush in the war in Iraq, with one million taking to the streets of London in 2003, and some, in the years that followed, branding him a war criminal.

Google, Dolly the Sheep and GTA

The internet era was in its infancy. The domain Google.com was registered in September, and an IBM computer called Deep Blue beat world chess champion Garry Kasparov. Meantime, the cloning of Dolly the Sheep shocked the world.

Microsoft was the world’s most valuable company and Steve Jobs went back to Apple, while the release of the original Grand Theft Auto marked the start of a gaming franchise.

The Kyoto Protocol, marking significant global efforts to combat climate change, was signed in December.

In his book The Nineties, the American writer Chuck Klosterman writes: “It was the end of twentieth century but also the end of an age when we controlled technology more than technology controlled us.”

Read more:

Why this election has shattered records

Meet Victoria, Sir Keir Starmer’s wife

Labour have won – but what happens next?

‘Boomers, beware!’

After Baby Boomers and before Millennials, Generation X comprised roughly people born between 1965 and 1980, and was named after a novel by Canadian author Douglas Coupland at the start of the 1990s.

Also known as the MTV generation and immortalised in the American movie Reality Bites, GenXers are typically defined as apathetic, nihilistic and prone to cynicism and self-deprecation.

“The twenty-something generation is balking at work, marriage and baby-boomer values,” Time magazine wrote in 1990.

“They would rather hike in the Himalayas than climb a corporate ladder. They have few heroes, no anthems, no style they call their own.”

In 1997 however, Time revised its assessment to describe a more hopeful, active cohort.

“They are flocking to technology start-ups, founding small businesses and even taking up causes-all in their own way. They are making waves on the Web, making movies in and out of Hollywood, making money, spending money,” it wrote.

“Slapped with the label Generation X, they’ve turned the tag into a badge of honor. They are X-citing, X-igent, X-pansive. They’re the next big thing.

“Boomers, beware! It’s payback time.”

End of the British Empire

Newly elected, Blair attended the handover of Hong Kong, Britain’s last remaining colony, to China, a historic transfer of power that brought an end to the British Empire.

The Berlin Wall had fallen and 9/11 was yet to happen – but the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s were the bloodiest conflict in Europe since the Second World War.

Britain was still part of the EU, and, across the Atlantic, the White House was occupied by a 50-year-old Democratic president and kindred spirit, Bill Clinton.

Russia, with Boris Yeltsin in the Kremlin and oligarchs running wild, was admitted to international gatherings, and Blair himself visited Yeltsin in Moscow that year.

No honeymoon for Starmer?

The state of the economy and his own popularity allowed Blair to enjoy a honeymoon period.

“I do not expect that Starmer will be so lucky,” says Boulton. “Bitterness and division have soured British politics this century.

“From day one he will be under attack for the state of schools, NHS, migration, which he has inherited.”

But, Boulton adds Labour is better prepared for government this time, pointing to Sir Keir’s chief of staff (the experienced Sue Gray) and his own expertise as an administrator during his stint as the Director of Prosecution Service.

“I expect a period of great unpopularity for the new Labour government but Stamer may have the qualities to pull through it,” he says.

The Latest News

-

December 22, 2024Donald Trump picks Apprentice producer to be the US special envoy to UK

-

December 22, 2024Daily horoscope: December 22, 2024 astrological predictions for your star sign

-

December 21, 2024UK flights and ferries cancelled owing to high winds as Christmas getaway begins

-

December 21, 2024Prince Andrew plans to move to UAE amid espionage allegations: Report

-

December 21, 2024Inside Britain’s saddest shopping centre: Town centre mall empty just DAYS before Christmas as depressed locals say ‘it’s a disgrace’