U.K. election live updates: Incumbent Sunak pitted against Starmer as Britain votes

- by Admin

- July 4, 2024

Who is British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak?

Reporting from Richmond, England

Rishi Sunak has a habit of making history. He’s the United Kingdom’s first British Indian prime minister and its first Hindu leader, and at 42 he was the youngest to take the job in over 200 years. He’s also probably the richest person to govern from No. 10 Downing St.

Now 44, Sunak is about to mark new records in the U.K. general election today.

Hanging over the electorate is a feeling that there is one set of rules for the elites in London — and another for the rest of Britain after years of Conservative Party rule. Living standards are being squeezed. The gap between the very rich and the rest has continued to widen. There is the widespread perception that public services not just are struggling but are on the verge of failing.

Broadcasting rules: Why the U.K. regulator tells media to stay quiet during the vote

In an effort to make sure that political coverage is impartial on election day, the U.K.’s state broadcasting regulator, Ofcom, is strict about what media outlets based in Britain can and can’t say while the country’s voting.

Because NBC News’ London bureau is covering the election, we’ll be upholding these rules.

They include avoiding direct discussion of issues, individuals and polling related to the election. While content published before voting began is allowed, outlets aren’t allowed to publish anything new on the day of the vote.

But when voting closes, though, the gloves are off.

The British system: How voting works in the U.K.

The U.K. general election is very different from its U.S. equivalent in that the British ballot elects both the executive and the legislature at once. In the states, the president and Congress are voted for separately; in Britain, the whole thing is effectively bundled up together.

The British version isn’t a single vote but rather 650 mini-elections held across the country. The results of those 650 counts won’t be confirmed until the early hours of tomorrow morning, with some tight races or races in remote parts of the country delayed until much later that day.

Each of the 650 mini-elections selects one lawmaker to send to the House of Commons. And if one party manages to get more than half of the members of Parliament, or MPs, it can form a government. That party’s leader, also an MP, usually becomes prime minister, who selects Cabinet members mostly from other elected lawmakers.

If no party wins a majority, coalition negotiations begin.

Britain decides: Upstarts and also-rans

Sunak and Starmer aren’t the only ones competing.

Reform U.K. is a right-wing populist group spearheaded by Donald Trump ally Nigel Farage. The Scottish National Party hopes to hold onto its dominance in Scotland. And Ed Davey’s Liberal Democrats will look to make gains elsewhere. The Greens and Wales’ Plaid Cymru are also fielding candidates and have won single-digit hauls of seats in the past.

Although Britain is often considered a two-party system, these historically smaller groups could be called on to form a coalition if neither the Conservatives nor Labour win enough seats to govern alone. That was the case in 2017, when Conservative leader Theresa May failed to amass enough votes and was forced to enter an informal coalition with the Democratic Unionist Party of Northern Ireland.

Northern Ireland is something of an anomaly in that the mainstream British parties don’t have much of a presence there; in their stead the DUP, Sinn Fein and others are mostly drawn along sectarian lines. No such coalition shenanigans were necessary at the last election in 2019, when Johnson won a convincing majority against Jeremy Corbyn, who led Labour at the time.

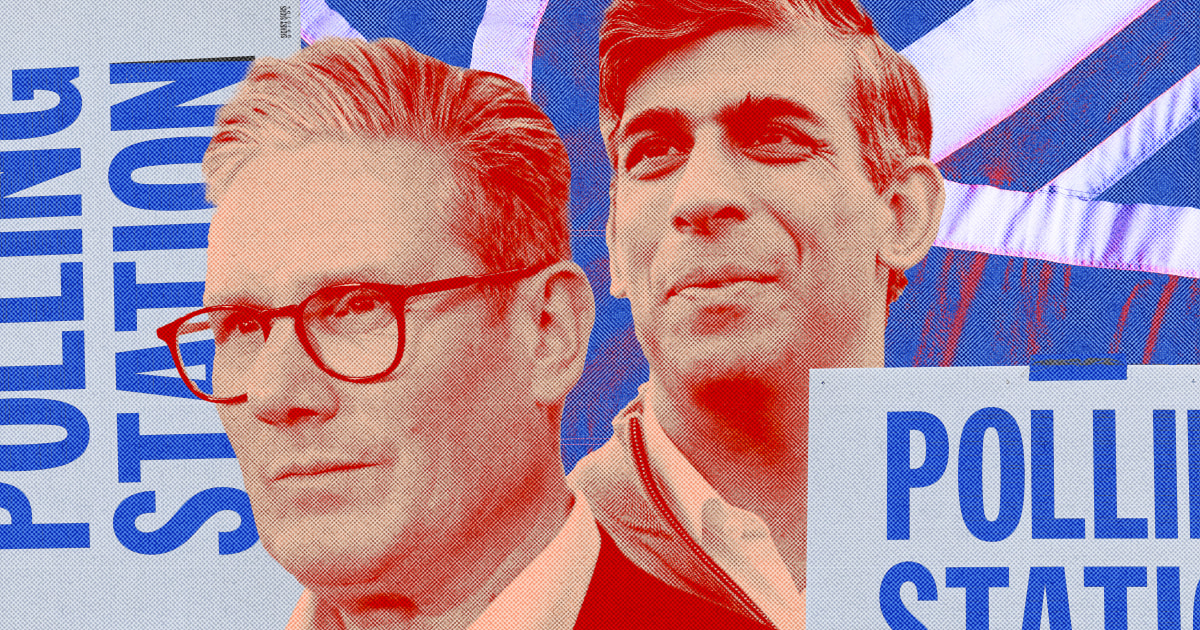

The main contenders: In the blue and red corners

Millions of Britons began voting today in an election principally between the Conservative government of 14 years and its Labour Party opposition. Unlike in the US, the Conservatives, which lean right, are represented by the color blue. Labour, meanwhile, are represented by red — historically the color of the international left-wing movement.

The Conservatives are led by Sunak, 44, who became leader in 2022 without a public vote after his predecessors, Boris Johnson and then Liz Truss, resigned in quick succession.

Labour is headed up by Starmer, 61, a former prosecutor and human rights lawyer who hopes to become the party’s first national leader since Gordon Brown was defeated way back in 2010.

This year, the election is being fought on the battleground of the economy. Britain has stagnated in recent years, battling high inflation and flatlining wages compounded by its acrimonious departure from the European Union. Other big issues, voters say, are the National Health Service, a beloved, publicly funded institution that’s perpetually on the brink of collapse, and immigration.

The Latest News

-

December 22, 2024Donald Trump picks Apprentice producer to be the US special envoy to UK

-

December 22, 2024Daily horoscope: December 22, 2024 astrological predictions for your star sign

-

December 21, 2024UK flights and ferries cancelled owing to high winds as Christmas getaway begins

-

December 21, 2024Prince Andrew plans to move to UAE amid espionage allegations: Report

-

December 21, 2024Inside Britain’s saddest shopping centre: Town centre mall empty just DAYS before Christmas as depressed locals say ‘it’s a disgrace’